In November 1930 an exhibition took place in the New Horticultural Hall, Westminster, London that was titled, ‘The Bachelor Girls Exhibition’. According to Fiona Anne Seaton Hackney’s 2010 thesis on ‘Feminine modernity and the feminine imagination in women’s magazines 1919-1939’, the ‘bachelor girl’ or youthful secretary, represented the possibilities and perils of modern life, and became a familiar figure in magazine advertising in the 1920s.

Reports of the Bachelor Girls’ Exhibition reached around the world, and the following report appeared on the front page of The Advocate (North-Western Tasmania’s daily newspaper) on Monday 28 July 1930;

“BACHELOR GIRLS. Exhibition at Westminster. SYMBOLS OF “SLAVERY”

London, Saturday – No man, unless accompanied by a woman, will be admitted to the Bachelor Girls’ Exhibition, to be held at Westminster in the autumn. The show will be completely staffed by women, including women police. Bachelor girls’ food, clothes, books, toilet and amusements will be represented in various sections, one of the most interesting of which will be a woman’s “chamber of horrors”, displaying all the tortures from a ducking stool to boned collars and steel corsets, to which women were formerly subjected. The organisers hope thereby to make young women enjoy their dearly-won freedom and independence, and realise the sufferings endured by previous generations.”

The Bachelor Girls Electrical Home

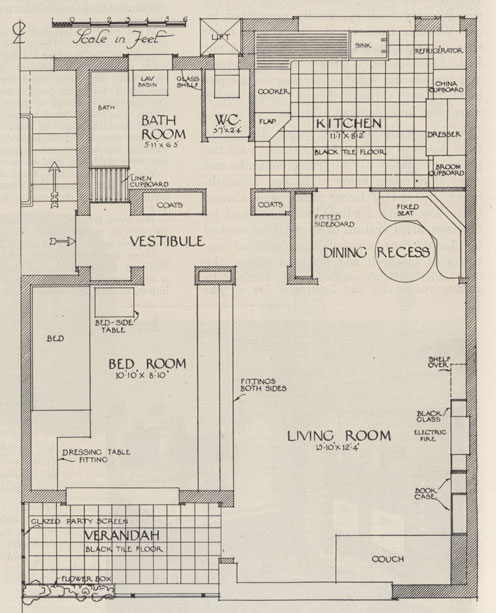

At the Bachelor Girls Exhibition the Electrical Association of Women (EAW) organised a demonstration flat that according to the EAW was the first public expression of a woman’s idea of how the bachelor woman could live electrically. A scale plan of the Bachelor Girl’s All-Electric Flat is shown below.

The flat, while planned as an exhibition stand, was considered as one unit of a block, the plan of the complete block being shown on the outside of the flat. The flat was designed by Miss Edna Moseley (sic), ARIBA, and erected with the financial help of the British Electrical Development Association and other sections of the electrical industry. It consisted of a small hall, a sitting room, with a dining recess which also linked with a kitchen, a bedroom, bathroom, toilet, and sun balcony.

The sun balcony, or verandah, was discussed by the EAW in its journal, The Electrical Age, as follows;

“The verandah, where the Bachelor Girl can indulge in her love of flowers and where she can enjoy real sunshine in the summer and artificial sunlight in the winter, created great interest.”

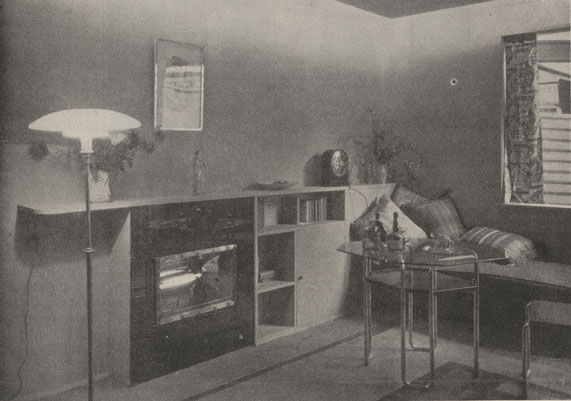

The image below shows a corner of the sitting room in the flat, showing the built-in electric fire.

Bachelor Girls’ Electric Flats at Highgate

The EAW journal had already touched upon the subject of all-electric flats for bachelor girls in an article by Dorothy E Edgecombe titled, ‘Bachelor girls’ electric flats at Highgate’ which appeared in the October 1930 issue of The Electrical Age. The flats in question were located in half-timbered Tudor-style buildings in Makepeace Avenue, Highgate, where the flats themselves were owned by Lady Workers’ Homes Ltd.

Dorothy describes a visit to her friend Mary who lived in one of the all-electric flats. After describing the lighting and contents of the flat Dorothy asked Mary whether ‘using all this electricity must cost you a small fortune’, to which Mary replied;

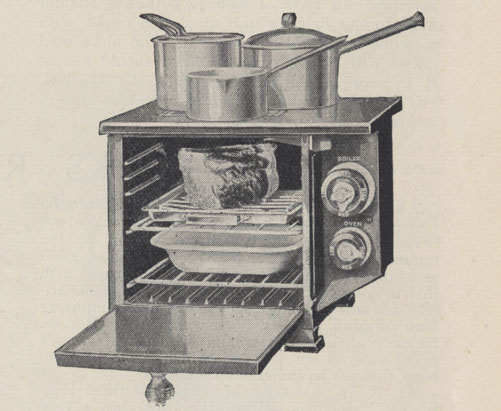

“Not when you are dealing with a progressive body like the St Pancras Corporation. They only charge a flat rate of ½d per unit for everything, so that even on my small income I need not think twice about using all these gadgets. Even my little “Baby Belling” cooker doesn’t run my bills up too high, as it is specially designed to use as little current as possible”. The image of the Baby Belling that Mary used in her flat appeared in the article and is shown below.

The block of flats in Makepeace Avenue still survive to this day although no longer owned by Lady Workers’ Homes Ltd. As the bedsit rooms and flats were built without kitchens a block was built nearby at 30 Makepeace Avenue to serve as a centre for the community and included a restaurant, reading and meeting rooms and a small theatre (this block was demolished in the 1950s). Camden Council for many years retained the policy of only placing women in these flats but this policy has since lapsed. The photographs below show Makepeace Avenue and the Makepeace Avenue flats as they are today.

Women and Property in the 1920s and 1930s

A resurgence of interest of women in property in the 1920s and 1930s is perhaps also unsurprising given that it was only in the 1920s that women achieved parity with men as regards owning and disposing of property in the UK.

Until the late 19th century, women who held property of any kind were required to give up all rights to it to their husbands on marriage. However, a long-running campaign by various women’s groups led in 1870 to the Married Women’s Property Act. This allowed any money which a woman earned to be treated as her own property, and not her husband’s.

Further campaigning resulted in an extension of this law in 1882 to allow married women to have complete personal control over all of their property. In 1922, the Law of Property Act enabled a husband and wife to inherit each other’s property, and also granted them equal rights to inherit the property of intestate children. Then finally, under legislation passed in 1926, women were allowed to hold and dispose of property on the same terms as men.

For those wishing to read more about the ‘Bachelor Girl’s All-Electric Flat’ in The Electrical Age, this is part of the archives of the Electrical Association of Women held in the IET Archives at Savoy Hill House (collection reference NAEST 93), which are available to consult by appointment.

Leave a comment